JOURNAL OF GENIUS AND EMINENCE, 5 (1) 2020

Effective Collaboration between Professional

Polish Filmmakers:The Grounded Theory Approach

Aleksandra Zienowicz-Wielebska

Jagiellonian University, Poland

Aleksandra Krukowska-Burke

Newman University, United Kingdom

Ewa Serwotka & Pola Weiner

Positive Sport Foundation, Poland

Abstract

Psychological factors such as achievement motivation and personality affect individuals involved in film production. Group dynamics are also highly influential during the filmmaking process, yet studies in the performing arts are limited in number, and few have focused on the psychological needs and the complexities of the film production crew which contribute to achieving a high-quality masterpiece. The present study aimed to explore the social contexts (factors and processes) in which eminent Polish filmmakers develop and flourish, using the performance psychology perspective. Twenty actors, 16 directors, 12 producers, six cameramen, five sound technicians, four costume designers, three make-up artists, three film editors, two screenwriters, and two stage designers participated in semi-structured interviews and participant observations. The resulting grounded theory of Effective Film Production Collaboration suggests that conditions (e.g. need for achievement) influence group- and individual-level factors (e.g. communication) which in turn affect the quality of collaboration, that is perceived through group cohesiveness, quality of relationships, and perseverance.

Keywords: Film, performance psychology, performing arts, effective collaboration, grounded theory

Film production is based on a collaboration of the members of many departments whose efforts combined can make a film successful (Hadida, 2009). For one person to make a movie alone is an impossible task (Simonton, 2009). Over a period of months, or sometimes even years, collaboration between and among directors, actors, scriptwriters, and other film co-creators is affected by the group dynamics (e.g. tensions, conflicts, and leadership). There are some studies in which the relationship between each member of a theatre crew was examined (e.g. actor-director relationship; Lennox & Rodosthenous, 2016). However, the relationships between different people involved in the making of a film have not been studied extensively (Mroz, Kociuba, & Osterloff, 2017). The performance psychology approach employed here can offer an interesting perspective on the collaboration between filmmakers at every level of performance, including the high level, eminent, and professional crews.

Performance psychology is a subdiscipline of psychology, dealing with scientific exploration of factors behind a repeated ability to deliver consistently high levels of performance in the domains where excellence matters, satisfaction with one’s performance, and the practical application of this knowledge (Hays, 2006; Portenga et al., 2011). As pointed out by Hays and Brown (2004, p. 19), performers “must meet certain performance standards: They are judged as to proficiency or excellence, there are consequences to poor performance, [and] good coping skills are intrinsic to excellent performance”. Performance psychology approach entails not only the development of mental skills (such as goal setting or imagery), but also building an effective professional philosophy which allows performers to consistently demonstrate extraordinary levels of performance (Portenga, Aoyagi, & Cohen, 2016). Performing artists, in all performing domains, face a number of performance issues, with the major ones being concern for high standards and excellence, competition, the role of emotion, memorization, the role of the audience, consequences to performance, and performance stress (Hays, 2017).

Athletes, artists, actors or musicians use a wide array of techniques and methods to cope with those issues and reliably demonstrate high level of complex motor skills. Eminent individuals in the domains of sport (i.e. Olympic medalists), media and creative arts or even medical services (e.g. Sarkar & Fletcher, 2014) have been studied from performance psychology perspective to understand what enables them to thrive and perform at extraordinary levels. For example, expert athletes have been found to show higher levels of cognitive flexibility (Richard, Abdulla, & Runco, 2017) and more proactive disposition (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2012) than their less successful and less skilled counterparts.

Within performing arts, the researchers can compare the similarities and differences of various pieces of art, for example in film or music, and how they are perceived and received by the audience (Cohen, 2002). However, looking more closely at the individual artist and their functioning is also worth attention. At first glance, it may seem that the performing arts domains are very different, but looking deeper at the mechanisms behind performing artists’ functioning, we can arrive at a number of analogies, which makes it possible to transfer the knowledge from, for example, the field of sports psychology to the world of art.

For instance, performers from different domains present their activity (they “give a performance” – both sportspeople during a competition and musicians or actors alike), they are subjected to exposure and social judgment (opinions of the audience, commentators, critics, media; Hays, 2002), employ their skills directly in their performance, use their body as a tool

(e.g. actors, operators, sportspeople, instrument-alists, surgeons), work in a stress-inducing freelance-mode model (e.g. directors, singers, make-up artists, motivational speakers) that requires them to be flexible and act quickly (Lubell, 1987).The performance itself is affected by similar factors, for instance: performer’s

physical and mental state on a given day, injuries and/or sickness, and the size of the audience. One of the biggest challenges faced by performers are: repeated physical effort (including overtraining) and stage fright (Clark, 1989).

It is important to add that despite many similarities, each performance domain functions based on laws and phenomena specific to a given domain (cf. Ayoagi et al., 2012; Hamilton & Robson, 2006). The method used to evaluate the final outcome constitutes one of the main differences between the various performance domains. Some domains within the performing arts can be characterized by a higher degree of subjectivism and arbitrariness of judgement than others (Solomon, Pruitt, & Insko, 1994; Zickar & Slaughter, 1999). The application of existing theoretical models from other domains could neglect significant factors that are present in the area of filmmaking.

The links between psychology and film are well known (e.g. Brol & Skorupa, 2018), and Young (2012) divided them into three categories: (1) the psychology of the filmmakers (i.e. explaining movies as a mirror of their makers’ psyche and professional psychological support for filmmakers to help them create movies), (2) the psychology in the movies – the way meaning is created in a film (e.g. psychological disorders in films), and (3) the psychology of the movie viewers (e.g. the emotions experienced whilst watching a particular movie). In the present study, the authors focused on the first category, as exploring the psychology of filmmakers (i.e. personality traits, achievement orientations, group dynamics, the mental habits of the elite) and the ways in which psychologists can provide professional support to the various members of a film crew constituted the focal point of the study.

The Filmmaking Process

In order to better understand the Polish film industry, a description of the stages of the filmmaking process has been provided below.

There are three main types of films: feature films, animated films, and documentary films. Films can cause various reactions in their audience (e.g. laughter, crying), cover different themes (e.g. war, crime), offer different forms (e.g. poetic, musical, adventure), use various settings (e.g. historical films, costume dramas), or distinctive iconography (e.g. westerns) (Loska, 1998). In the present article, the authors have focused on the specificity of the process of making a feature film in Poland, which encompasses different genres and types. A feature film may be based on actual events or be completely detached from the reality outside the script and the set (Wojnicka & Katafiasz, 2005). Making a feature film involves four main stages. The quality of the tasks carried out at the first stage affects the conditions and the possibility of carrying on with work at further stages. The main stages of feature film production are: 1) development – developing a film project, 2) pre-production – the period of preparations, 3) production – the period of principal photography, and 4) post-production – editing, scoring, and final development of a film. Further stages include: film distribution and exhibition (Hadida, 2009).

Film production collaboration is commonly understood to take place only on a film set (in the production period), but what happens before and after the shooting is also very important. For example, during the “pitch meetings”, the screenwriters and producers would discuss the potential film. Depending how those meetings proceed, the film may or may not receive the financial support of the producers (Elsbach & Kramer, 2003; Simonton, 2009). As noted by Ferriani, Corrado, and Boschetti (2005), everyone involved in the process of creating a movie provides their talent, genius, and expertise to fulfil their specific roles. They are usually organized within groups and subgroups, and even though the particular filmmakers are involved in the filmmaking process to different extents and at different stages, the element of collaboration is equally important at each stage to realize the potential of the project (Zienowicz & Serwotka, 2017).

According to Zablocki (2013), it usually takes 10-12 months to make a film in Poland. A film is always the result of collaboration between more than a dozen departments, where each department is responsible for specific tasks to be carried out and one department’s work depends on the work of another department; e.g. actors are dependent on the quality and pace of work of costume designers and make-up artists before they can even begin shooting scenes, and film editors are dependent on the quality of material provided by the cameramen. During filmmaking, the roles of particular departments should be clearly determined (e.g. the director sets the overall vision of the project, the producer deals with financial matters), and as the process enters further stages, the priorities in terms of crew significance change (e.g. after the shooting period the material is submitted for editing, where the key roles are played by the editor and the director) (Zablocki, 2013). According to Szmagalski (1998), the life of groups is a process of constant changes, and the extent to which such changes bring a group closer to the set objectives depends on the effectiveness of collaboration within the group.

A Film Production

Crew as a Team

As noted by Kogan (2002), in the domain of performing arts, it can be distinguished between creators and interpreters. Creators, such as screenwriters, create the works which are then interpreted through performance by the interpreters, such as actors. In a theatre setting, a creation of a playwriter may be replicated by actors in many theatres, various countries and even through centuries. On a film set, on the other hand, screenwriters may have a chance to collaborate with the only actors interpreting his or her writing for that specific project. Another distinction between creators and interpreters in the theatre lies in the privacy of their work; an artistic creator’s work is a relatively private activity whereas performing artists, generally, are members of a group or cast which is highly interdependent (Kogan, 2002). However, on a film set both groups: creators (e.g. music composers, costume designers) and interpreters (e.g. actors, sound technicians) often work closely together towards a common goal, success of which can be achieved through effective teamwork. High level of trust and appreciation from all team members are some of the factors which can affect the quality of such collaboration and make the desired outcome a reality. The work of a film production crew is based on the interactions, which means that one person’s work affects the work of another’s — the whole crew is a self-regulating system. The interactions between various members of a film production crew are characterized by specific dynamics and require certain adaptive skills, for example: reacting to difficulties or looking for solutions when financial problems occur (Zienowicz & Serwotka, 2017).

Cattani and Ferriani (2008) investigated the role social networks play in shaping the ability of individuals to create original work; the study examined this within the context of the Hollywood film industry over a period of nine years (1992–2003). The results have shown that the individuals most advantageously positioned to achieve positive creative outcomes are those who hold an intermediate position between the core and the periphery of their social system. The focus of this study was creativity, and instead of looking at creative individuals as it has been done in many previous studies (e.g. Montuori & Purser, 1996), the authors took a social networks approach by acknowledging that the social and contextual factors affect the creative outputs of individuals. According to other authors (e.g. Simonton, 1984a; Brass, 1995; Csíkszentmihályi, 1999), creativity flourishes within the interactions between a person (their cognitions and emotions) and their social-cultural context and is embedded within their relationships with others. Each film is unique; hence the creativity of its makers plays a role in the final success. As pointed out by Cattani and Ferriani (2008), “not only does the group constitute a fertile arena for stimulating productive thought, but its social structure also has important implications for how individual outcomes are perceived externally and hence supported” (p. 828).

If a performance psychologist wishes to support the collaboration between various members of the film crew, it is of paramount importance to understand the requirements of the different stages in the film production process as they affect the dynamics between the performers. The film crews act and function in a mutually complementary fashion, and as stated by Zablocki (2013, p. 138): “A film production crew is a kind of family, and it is special in that it functions to achieve a strictly specific common goal, that’s why in the literature, such crews are treated as teams”. A team is composed of people collaborating with each other in order to achieve an intended outcome (Salas, Dickinson, Converse, & Tannenbaum; 1992). A film production crew may be considered a team because the filmmaking process engages a whole group of people representing various departments. Such a model of collaboration involves quick exchange of information between individual members, coordination of multiple activities (specific for a given crew and related to the need to create a film), a constant readiness to adapt to the requirements of a particular task and establishing an appropriate organizational structure (Zienowicz & Serwotka, 2017).

A concept closely related to group functioning is group cohesion as it concerns crew members’ opinions regarding their abilities to achieve goals, carry out certain tasks (Short, Sullivan, & Feltz, 2005), as well as the social (e.g. the closeness of relationships among the film staff) and the task-related elements on the way to a particular objective. Group cohesion is perceived on both individual and group levels, and it affects the degree of an individual’s involvement and readiness to sacrifice oneself to let the whole group achieve a goal (e.g. Carron, Widmeyer, & Brawley, 1985). The concept of cohesion is also very important in the filmmaking process, which is why when assessing the effectiveness of a film production crew, it is not enough to merely analyze the contribution of particular individuals (e.g. a given actor, member of the make-up crew, etc.). Film production crew effectiveness should be considered on a group level (see: Tesluk, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 1997), i.e. the interactions between all members of the crew should be examined; it is also necessary to contemplate the quality of the relationships between the departments. Only a more holistic perspective will make it possible to understand the dynamics that: occur in the process of filmmaking, influence the effectiveness of all people and crews engaged in the whole project, and create an environment in which creativity and eminence can flourish.

When looking at various members of a film crew and their functions, it is visible that their performances are interconnected, and the contribution of an individual (e.g. their charisma, achievement motivation, eminence, the level of respect for others) may spark the productivity of others. In many creative industries, the final outcome depends on the complementary skills of various contributors (Caves, 2000), but also on how well those contributors work together – on the quality of the relationships they build and nurture (Ferriani et al., 2005). Aspects such as mutual trust, effective communication or appreciation are key in maintaining effective partnerships; however, there is a limited number of studies which looked at the quality of collaboration from a broader perspective of a film crew (not just actors-directors), or what other psycho-social factors may affect the quality of the relationships and by that, the effectiveness and success of a whole film production project (understood as a creation of a high quality film). In a study by Ferriani and colleagues (2005), the authors found patterns of enduring collaboration between individuals involved in a film production (i.e. in a core team and sound crew) and have indicated the importance of interpersonal ties. However, it was noted that in order to understand the micro-processes in which the patterns are grounded, a qualitative approach was needed as such methodology would allow to delve into the social processes and complexities existing during a creation of a motion picture.

Effective Collaboration of Members of a Film Production Crew in Practice

The starting point of, and the inspiration behind, the discussion on the effectiveness of collaboration between filmmakers was a letter by the Management Board of the Polish Audiovisual Producers Chamber of Commerce (Zarzad KIPA, 2016), which stressed the significance of collaboration of departments’ representatives (e.g. the director and the scriptwriter) for the success of a film or TV projects. It was emphasized that the effective collaboration should be based on mutual trust as well as on predetermined specific common goals; however, the authors did not provide specific practical recommendations to what actions are needed in order to achieve a high level of collaboration.

The above-mentioned letter stresses that the activity of a producer and a director should be cohesive and oriented on the success of the film. It is important to bear in mind that the standards of work are imposed by the director, who is primarily responsible for the course of action when working on a film project (Zickar & Slaughter, 1999). Film directors are the primary decision makers throughout the process of shooting a film, they are tasked with making creative and informed choices which can be greatly affected by the time pressure or the emotions experienced by the directors. In a study by Coget, Haag and Gibson (2011), results showed that emotions can affect the depth of processing when making important decisions: more deliberate and rational decision-making was influenced by a moderate level of fear, a moderate level of anger prompted expert-intuitive decision-making, whereas high intensity fear or anger combined with a lack of previous knowledge of a given situation resulted in emotional-intuitive decision-making. Even though the study explored an important factor affecting directors’ work (i.e. emotions), it was conducted from an individualistic perspective, whereas studies in the domain of social psychology and sport have shown that both emotions and mood are affected by the interactions with other people (e.g. Sullins, 1991; Totterdell, 2011).

Soila-Wadman and Koping (2009) analyzed leadership in film crews and symphony orchestras. In their study, the directors and conductors were not portrayed as individualistic heroes but rather, as a part of the team. From this perspective, the whole group was viewed as the “hero”. The filmmakers act and function in a mutually complementary fashion, following the director’s idea. By engaging the right team members, through the awareness of the competencies of particular filmmakers, by inspiring a sense of collectivity and team spirit, and through building relationships, a film comes into being. The director can influence the extent to which the crew will follow their vision; however, this does not change the fact that each person involved in the project can and should act to the benefit of the film, given the relationships between particular departments determine the effectiveness of the whole project. This is, of course, affected by other factors as well, e.g. the quality of the script or the amount of available funds.

In practice, some filmmakers may feel underestimated and viewed as individuals who do not contribute to the film project. This is expressed in the content of “An Open Letter from your Sound Department” (Coffey et al., 2014). The document was written by audio professionals working on film sets, and aimed to draw the attention of, for example, producers and directors to the fact that the work of audio professionals was also a vital component of a successful film. They provide a clear explanation of the nature of their work, and highlight the necessity for collaboration, which shall be based on established smooth and transparent borders of the scope of activities to be carried out by particular specialized crews, so that these crews can complement each other and work effectively towards a common goal — i.e. creation of a film.

According to the data included in the “Assessment of competencies in the film industry – between the industry’s needs and the education opportunities” (ECORYS Poland, 2016), ordered by the Polish Film Institute, it appears that representatives of particular filmmaking professions are concerned with the significance of social and interpersonal skills in their practice. What is more, the presented data show that filmmakers consider personal and social skills comparable to specialist qualifications. The following competencies are regarded especially valuable:

“determination in the pursuit of one’s goals, ability to predict the effects of the actions taken, openness to change, ability to manage stress, willingness to update one’s knowledge and to improve one’s professional skills. Respondents considered social competence equally significant, i.e. manners, observing the principles of ethics, trade secrets, taking responsibility for the actions taken, and ability to negotiate agreements. This is where competencies related to the ability to work in a team or to the knowledge of principles of effective communication were named as particularly important. The style, the nature, and the pace of work typical of this industry all make the ability to handle time and peer pressure as well as sensory overload fundamental to many professions. Frequent interactions between crew members offstage make the competency connected to establishing and maintaining good relationships extremely important”. (ECORYS Poland, 2016, p. 374).

Objectives and

Relevance of the Study

There is a very limited number of studies exploring the psychological factors of the film production environment in Poland (e.g. Mroz, 2008; 2015; 2017). The presented literature review has also demonstrated that many of the studies exploring the psychological factors in a film setting investigated them predominantly from the perspective of an individual filmmaker or a dyadic perspective. However, as film projects are based on a collaboration between numerous individuals who are each affected by the group dynamics (e.g. team cohesion, emotional contagion), the present study aimed to explore the factors which contribute to effective teamwork within groups of filmmakers, and which ultimately allow filmmakers to thrive and showcase their eminence, genius, and talent in creating high quality films. Moreover, to the authors’ best knowledge, there are no studies that have looked into the social processes and complexities that characterize film production crew from the perspective of performance psychology. As suggested by Ayoagi et al. (2012), and Hamilton and Robson (2006), performance psychologists should aim to understand the specific performance domain prior to commencing a collaboration with performers.

At the outset of the present project, the researchers conducted several informal conversations with people engaged in film production and with the deans as well as students of three major film academies in Poland. The filmmakers were requested to partake in informal conversations during various film festivals. The first group consisted mainly of established actors and directors. The deans of the Acting, Production, and Directing departments of the most prestigious Polish film academies participated in these talks as well. Finally, students representing numerous departments (e.g. Acting, Directing, Animation, Operating, Editing) and who were at various stages of their education, also contributed to these informal conversations. As immersion into the participants’ environment allows the researcher to better understand the processes and factors involved, those initial meetings constituted a chance to learn about the specifics. What more, those conversations allowed them to understand the variety of roles and responsibilities involved in a film production crew (e.g. the responsibilities of directors versus producers) and the stages of the film production process. Moreover, these activities supported the formation of the subsequent research ideas. Every participant of informal conversations expressed their desire for greater understanding of the psychological demands that affect them.

Given the above, the need to better understand the film environment voiced by some filmmakers, and a lack of coherent guidance to provide psychological support to filmmakers in Poland, a qualitative approach was chosen – specifically, a grounded theory approach. The researchers aimed to explore the social processes and complexities specific to the process of film production in a single country, considering the limitations and possibilities created by the governing bodies in that country.

Materials & Methods

Methodological Overview

Grounded theory constitutes an insightful approach to explore phenomena which have not been extensively studied and satisfactorily explored (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). According to Holt and Tamminen (2010) and Weed (2017), when considering using a grounded theory methodology, the researchers should examine their philosophical orientation and choose a variant of the grounded theory accordingly. Thus, in the present study Corbin and Strauss’ (1998, 2008) variant of grounded theory was used as it allows “insight, enhance understanding, and provide a meaningful guide to action” (Strauss & Corbin, 1998, p.12). The techniques and procedures were employed in accordance with the post-positivist beliefs (cf. Weed, 2009).

Participants and Sampling

Initially, participants were recruited through purposive sampling, in which the researchers focused on the more experienced and knowledgeable members of a film production crew, specifically the directors and producers, as well as actors. The directors and producers tend to have the broadest perception of the collaboration between members of a film crew, as it is their responsibility to select with whom they want to create a film (Zablocki, 2013). Actors are usually the group, whom, among the filmmakers, are the most open to seek psychological support. Most of the participants were award-winning filmmakers in Poland and abroad. Among them there are award-winning filmmakers who have been recognised by various prestigious institutions and at major film festivals, including: Academy Awards (Oscars), American Association of Cinematographers Venice Film Festival (Lions, Gold Osella), Berlinale (Bears), International Film Festival in Locarno (Leopards), Polish Film Festival (Eagles), Karlovy Vary International Film Festival (,,East of West” Award), Los Angeles Film Awards, Brasilia International Film Festival, Montreal World Film Festival Award, International Short and Animation Film Festival, Worldwide Short Film Festival, Canadian Film Centre’s Worldwide Short Film Festival, Manlleu Short Film Festival, Norwich Film Festival (Amanda), Kosmorama Trondheim International Film Festival, and European Independent Film Awards (Grand OFF). The interviews and observations were employed with the aim to understand the specificity of filmmakers’ functioning and to gain insight into the complexities affecting a film production crew.

The data analysis from initial interviews and observations conducted on the films sets informed subsequent interviews, causing the process of data collection and analysis to intertwine (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). In the following stages, the selection of participants was directed by emerging concepts; thus, the participants were selected using theoretical sampling (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). This process commenced by sampling filmmakers serving other roles in the film production process (e.g. camera operators and film editors) and by conducting interviews with them. As the theory was taking shape, additional interviews with experienced filmmakers were scheduled, and more on-site, filmset observations were conducted. The final sample of participants consisted of: 20 actors, 16 directors, 12 producers, 6 cameramen, 5 sound technicians, 3 costume designers, 3 make-up artists, 3 film editors, 2 screenwriters, and 2 stage designers. All of the participants who took part in the study can be considered as elite in the Polish film setting; those filmmakers have won a number of awards both: nationally and internationally, and are regarded as experts in their specific departments. Moreover, the vast majority of them are the role models in the industry. Table 1 presents the demographic data of the participants.

Table 1

Demographic data of all the participants

|

|

New Technology |

Description |

Examples of choreographies where it had been used |

|

|

|

Age |

Years of Experience |

Gender |

|

|

Actors |

M = 44.8; SD = 13.9 |

M = 21.2; SD = 14.0 |

M = 12 |

F = 8 |

|

Directors |

M = 46.9; SD = 12.2 |

M = 20.8; SD = 11.9 |

M = 14 |

F = 2 |

|

Producers |

M = 50.3; SD = 14.9 |

M = 17.0; SD = 15.7 |

M = 8 |

F = 5 |

|

Cameramen |

M = 54.8; SD = 20.7 |

M = 26.5; SD = 19.2 |

M = 6 |

F = 0 |

|

Sound technicians |

M = 47.8; SD = 8.7 |

M = 20.0; SD = 7.8 |

M = 4 |

F = 1 |

|

Costume designers |

M = 67.0; SD = N/A |

M = 28.0; SD = 14.0 |

M = 0 |

F = 3 |

|

Make-up artists |

M = 58.0; SD = N/A |

M = 21.3; SD = 4.5 |

M = 1 |

F = 2 |

|

Editors |

M = 55.0; SD = 4.2 |

M = 26.7; SD = 5.1 |

M = 2 |

F = 1 |

|

Screenwriters |

M = 41.5; SD = 17.7 |

M = 16.0; SD = 9.9 |

M = 2 |

F = 0 |

|

Stage directors |

M = 58.5; SD = 7.8 |

M = 29.0; SD = 8.5 |

M = 1 |

F = 1 |

Data Collection and Analysis

The participants were contacted by email and by phone calls. During the initial contact, they were notified of the purpose of the study and what it entailed, and they were invited to participate in an interview; in addition, the researchers inquired about the possibility to visit various film sets and conduct observations. The participants who agreed to take part in the study were emailed to arrange a mutually convenient time and location. Informed consent was obtained before the data collection began. The data were collected in various settings, including film academies, film sets, and during film festivals.

Grounded theory involves “an iterative process based on the interaction of data collection and analysis, facilitated via theoretical sampling” (Holt & Tamminen, 2010, p. 410). In the present study, the data were collected during a period of three years using a variety of methods: semi-structured interviews (ranging in duration between 60 and 120 minutes), participant observations, informal conversation, and field notes. Various coding processes were employed; starting with the open coding during which the concepts were identified, compared and contrasted for similarities and differences, and their properties were described. Then, during axial coding, categories and subcategories were linked, which helped to refine and conceptualize the phenomena being studied (Strauss & Corbin, 1998; Corbin & Strauss, 2008). As the filmmakers revealed their stories and perceptions, the anecdotes and incidents were compared across the interviews of participants in the same roles (e.g. director A vs. director B), and across various roles (e.g. directors discussed their expectations of the actors, and actors’ perceptions of the directors’ expectations were compared). The continuous comparison enabled the researchers to refine and develop the concepts, which is in congruence with one of the core elements of grounded theory; the constant comparative method (Holt & Tamminen, 2010; Weed, 2017). During the data collection and analysis, memos were written to record the main researcher’s thoughts and interpretations and guide the final stage of data analysis, selective coding, during which the theory was integrated and refined. The data collection and analysis ended when the data saturation was reached, and any new insights stopped emerging (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Results

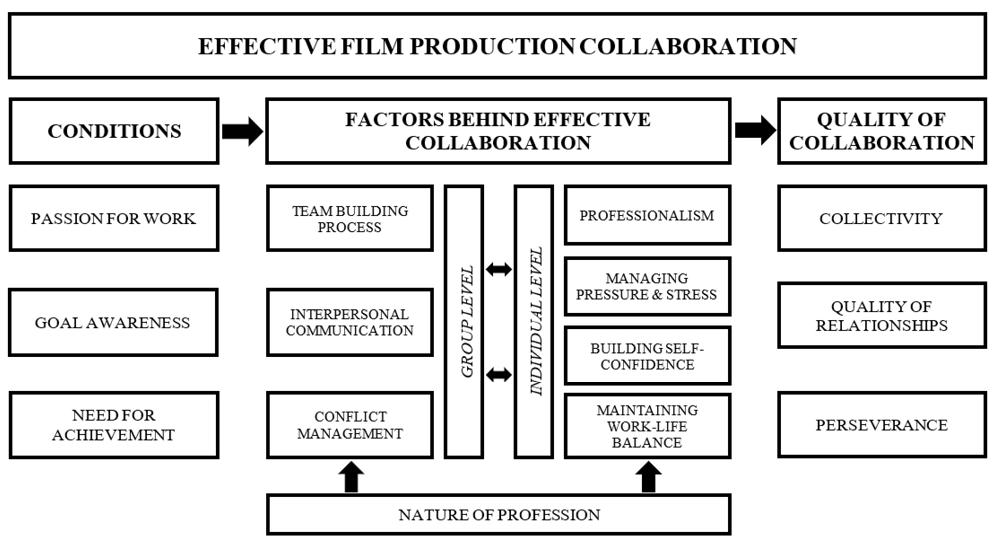

The analysis of the data led to the development of a grounded theory of effective collaboration between professional Polish filmmakers. In this section, the three main factors are presented and supported by participants’ quotes: 1) conditions (that form the structure of collaboration from the beginning of the creative process), 2) factors behind effective collaboration, and 3) quality of collaboration (including categories and subcategories that determine the level of effective collaboration and manifest themselves as a result of the impact of the factors described earlier, as a whole, these factors may contribute to high performance levels). In the presented grounded theory, the effective film production collaboration is an overarching concept which encompasses essential conditions, which may be understood as a mindset, through individual- and group-level factors, which contribute to reaching a certain level of cohesiveness of activity, and also direct indicators that the collaboration in the filmmaking process is effective. Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of the categories and factors to illustrate their connections.

Category: Conditions

The category Conditions represents elements which are important even before the film production starts. Those elements shape the attitude towards filmmaking and they provide certain mindset for all the filmmakers. This category includes three themes and it is assumed that without passion for filmmaking, goal awareness and need for achievement present at the beginning of a filmmaking process, it is arduous to persevere and achieve anything in this profession. Therefore, those three conditions not only allow effective film production collaboration, but they also support the filmmakers in their careers. Passion for work (a); according to filmmakers, passion makes it possible to initiate the filmmaking process and persevere throughout this process, especially in the face of obstacles as one of the participants explained:

“…. love for what you’re doing. Without it, there will be a moment when you’re too tired to survive it all. This feeling [love] will protect us in every situation, or almost every situation. It will remove the obstacle. It will support from within. It will help standing up and will give you joy” (Costume Designer 3).

Goal awareness (b), sets the course of action for all people engaged in the filmmaking process and supports effective and consistent collaboration of a film production crew. Even though individual goals should be valued and respected, it is of outmost importance for the filmmakers to be aware what the main goal is, to prioritize the actions that would bring the film crew closer to achieving that main group goal. When discussing various goals, many of the filmmakers admitted that they know they should be striving to support one another in achieving the main goal, that very often it is an implied expectation; one of the participants portrayed it this way:

“…. formal regulations are not enough. A sense of collective responsibility is necessary; additionally, it is important for everyone to be striving to achieve the best possible outcome. I believe that your aim is to work for the final result of the project, not your own outcome” (Film Editor 2).

Finally, (c) need for achievement, challenges filmmakers to engage in continuous growth and fuels their actions and sacrifice. The need for achievement is connected with the openness to new experiences, looking for unconventional solutions, and the attitude towards self-development. It also supports and drives the filmmakers in the lengthy process of creating a film where feedback and often gratification are delayed, and where creators have to wait months or sometimes years to see the final effects of their work. Need for achievement allows them to focus their actions and be productive, even without seeing the immediate effects of their work.

Category: Factors Behind

Effective Collaboration

The second category is divided into two levels (a) group level and (b) individual level. The group level represents factors used to interact with others in order to work effectively. Creating and making a film requires involvement of many people; therefore, it is important to account for the factors which affect the interactions among the filmmakers. Individual level encapsulates individual’s attempts to optimize their functioning, which in effect contributes to an increase in the level of effectiveness of the whole group’s performance. The factors from both group and individual levels affect each other and in addition are shaped by the nature of the profession of a given filmmaker.

Group level factors include: (a) team building process; it refers to choosing the right people to work with to create a film, with the selection resulting from the producer’s or the director’s knowledge regarding necessary competencies1, the tasks to be carried out, and the workstyles of particular filmmakers. The team building process is greatly affected by the crew members’ awareness of the functions performed by each of them individually and together in the group, of their mutual expectations and of their faith in the project from the start to the end. One of the participants said:

“I’m for 100% clarity. Every person from my department knows what they are supposed to do. I define my responsibilities and the character of my work very clearly. I am convinced that if you don’t clearly and honestly say who is responsible for what, chaos and frustration will appear” (Producer 11).

Interpersonal communication (b) is viewed by the filmmakers as readiness to search for a common ground for agreement, i.e. an “access key” to particular crew members at different stages of the filmmaking process. Filmmakers stress that an element of effective film production collaboration is creative dialogue (based on partnerships), which involves direct communication, active listening and feedback, or being open to collaborators’ opinions. As one of the sound technicians (Sound Technician 3) suggested:

“Communication is the foundation [base?], the ability to listen to the director and being able to do what is expected of us. It is important to remember that we’re making his [director’s] film. We always try to use our means to achieve what he [director] wants; there can’t be a situation that by using different means we will try to achieve something different and try to convince the director that this is really better.”

Moreover, an inseparable part of a film production crew’s work is an assertive attitude to collaborators, understood as the ability to react appropriately to different situations, taking the context into account while remaining aware of one’s and others’ rights and acting according to one’s own principles. Finally, conflict management (c) is a crucial factor allowing a film crew to successfully negotiate conflict. Filmmakers, drawing from their own experience, know that a conflict may spark an element of creativity and may result in reinforcement of collaboration of the whole team if treated as a difference of opinion, not as a personal attack. A quote provided by one the participants illustrates such productive approach:

“It is important for the filmmakers to not treat the pursuit for a high quality [of a film] as a fight, but instead, as a dialogue. I think it is important to talk, not to take offence. I believe that a conflict should not be treated personally but as a step which, if taken correctly, allows to forward progress” (Film Editor 1).

Individual level factors include: (a) professionalism, (b) managing pressure and stress, (c) building self-confidence, and (d) maintaining a work-life balance. Professionalism (a) refers to preparation (e.g. becoming familiar with the script), diligent work ethic, and commitment to the duties assigned. Furthermore, positive attitude, workflow and time organization, and focus on the tasks at hand all benefit effective collaboration. In order for a film production crew to be able to work effectively, it is necessary to define the meaning of professionalism in the context of a particular group; it can be understood differently at the individual level, though. Managing pressure and stress (b) includes the ability to handle the opinions of collaborators, media, or society. A filmmaker’s career is dynamic and changeable, it involves both success and failure, which both may have similar effects on the mental state of a given creator. That’s why it is so important for filmmakers to be able to deal with various stressors because their profession involves a sense of a constant uncertainty. The following quote highlights the psychological demands which the filmmaking process inflicts on the filmmakers:

“Stress occurs in every stage of the filmmaking process: doubts if the project will even commence; new situations at the beginning of the production; communication with new collaborators; stress whether the intellectual, health and artistic resources are enough to make the project successful; and finally, stress connected with film editing and then with detaching yourself from the film when you await viewers’ reactions” (Director 4).

Building self-confidence (c) understood as an active approach to building one’s sense of confidence, entails acting within one’s limits and according to one’s principles, analyzing one’s own performance, and engaging in self-reflection. It also means an ability to draw conclusions and learn from mistakes, as well as an awareness of one’s strengths and weaknesses as one of the participants disclosed:

“Failures do happen and then you have to replay your journey and consider what went wrong. If a person believes that what they’re working towards will happen, then this process is easier because we have more strength (Costume Designer 3).

A filmmaker who is sure of their competencies and of the role they play in a film production crew improves their ability to make decisions and to accept the potential risks such decisions involve.

Maintaining a work-life balance (d) refers to the ability to control energy resources, e.g. taking care of one’s physical and mental balance. It involves the need to release the tension after the production is complete (e.g. when it’s time to face the reality after a project ends, searching for balance) and taking care of one’s relationships with friends and family, which also can constitute a great source of support; one of the participants reflected that:

“Acting gives you an opportunity to have a parallel life. Your family is your real life, and in my case, my family gives me perspective and distance [from work]. My second life is the one I live on a film set, in my little film community” (Actress 1).

This is especially important in the context of the specificity of the profession of filmmaker, where high-intensity periods alternate with phases of dormancy (understood as e.g. non-participation in a project).

Filmmakers are aware of the difficulties inherent in their profession. Both the group-level and individual-level factors referred to above are shaped in response to the nature of their profession. In their everyday practice, they face many situations that are standard elements of their work, e.g. fear of idleness (e.g. not making it through a casting and thus not getting hired for a film), the unpredictability of their profession (e.g. a co-producer withdraws from the project), living in two parallel worlds (i.e. personal and professional), the need to be flexible (e.g. seven days a week, irregular working hours), subjective assessment of their performance (e.g. reviews or audience rating), or time and financial pressures. Being aware of the factors that derive from the nature of filmmakers’ professions allows them to be better equipped and prepared to face the everyday challenges of the production phase.

Quality of Collaboration

The final category includes (a) collectivity, understood as a situation when film production crew’s working standards are imposed by the director, and the job of particular crew members is to understand and follow clearly defined directions within the collaboration. The quality of collaboration also much depends on the crew’s awareness regarding the goal to be pursued, and on the sense of individual responsibility for the final outcome of the pursuit (e.g. particular crew members being responsible for the decisions taken and facing the consequences of these decisions). In order to optimize the workflow and proceed according to the production strip board22, it is important that all crew members be familiar with the tasks that need to be carried out by each of them, stick to their qualifications, be able to distance themselves (e.g. from their ideas, including the ability to withdraw from them if they appear to be of no good to the film), and be able to tackle difficulties and look for solutions together. Of immense importance is the role of a director, who is in a privileged position to influence the sense of collectivity as this quote illustrates:

“The filmmakers are more likely to collaborate effectively if they like the project. I have always believed that a director must inspire the collaborators, he [a director] has to care to ‘infect’ others. It’s a bit like being a commander, a leader. If a leader doesn’t believe in a victory, then the followers will not believe they can succeed. It would affect their morale without a doubt” (Director 16).

Another element is the quality of relationships (b); filmmakers stressed that a partnership approach, readiness to show support, and the ability to accept mistakes made in the course of the filmmaking process favour collaboration and creative success. Moreover, an authentic and empathetic attitude, trust, openness to collaboration, and respecting collaborators and their work all contribute to building relationships between individual filmmakers, as one of the participants said:

“…. in the meantime, little gestures cost only three minutes, but they so positively influence our work and collaboration (Make-up Artist 1).

Also, appreciating the contribution of particular crew members by providing positive reinforcement translates into their engagement and perseverance in pursuing a given goal.

The last element involves perseverance (c), meaning: determination, persistence, consistent behavior, patience, and readiness to engage in hard physical and mental work in the face of challenges filmmakers encounter in their everyday practice. The following quotes from two leading directors illustrate the significance of perseverance:

“Apart from successes, there is the everydayness – regular training which entails setting aims and goals for yourself without the support of fans, without the applause – as if you were in solitude. That’s the reality of working on a script, and before that, searching for a topic. That’s also the reality when you apply for funding and when you try to convince various institutions to finance your project” (Director 3) and

“I think that a so-called talent is only worth fifteen percent in my profession, the rest is stubbornness, persevering, and having the constitution of a horse. I believe that without perseverance it won’t be possible to achieve what you have planned. If I decide to do a certain film, then I will push until the end and not allow myself to be discouraged by, for example, lack of money” (Director 15).

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, the present study constitutes a first attempt to explore the functioning of various roles engaged in the film production process. The perceptions of the psycho-social processes and complexities which contribute to effective collaboration among various film departments (e.g. directors, cameramen, or costume designers) were investigated in the present study. The study was conducted from the perspective of performance psychology (e.g. Hays & Brown, 2004) and was focused on the positive and supportive factors which contribute to people’s growth and high level of functioning. Furthermore, the study was conducted within a single nation and therefore, the results are also grounded in the specificity of that country’s film environment (e.g. regulations, budgeting, actors’ education).

One of the participants, a film editor, said that: “A collaboration [during film production] starts where there is an awareness that I’m dependent on others, and others are dependent on me. It is due to the fact that the responsibilities of various roles interlock and overlap” (Film Editor 1). The collaboration between the filmmakers during the process of creating a film can be considered as more than the sum of all the efforts various members contribute to the process; the individuals coordinate their beliefs, thoughts, and actions to achieve a higher-order system which may lead to the final success. Every filmmaker brings their own dynamic (e.g. power, commitment, self-reflection) and engage with various mechanisms of mutual influence (Nowak & Vallacher, 1998; Zienowicz & Serwotka, 2017), in order to meet the demands and expectations of the project. As the participants noted, the factors which affect the interactions between the members of a film production crew are dynamic and time-sensitive (dependent on the stage of film production), dominant on an individual or group levels, and they are influenced by the characteristics of the industry (i.e. lack of full-time employment; being exposed to public criticism; or the need to both: immerse in the character and be able leave it when in personal setting).

Within the main system, some members create smaller sub-systems to increase the effectiveness of the project; for example, producers and directors work closely to be able to convey the vision of the film within the bounds of the accumulated budget. The EFPC grounded theory does not indicate which departments are more important than others. Rather, it highlights the importance of all the departments, and accentuates the importance of building and cultivating effective interpersonal relationships. Kogan (2002) stated that performing artists usually constitute members of a team and in order to achieve a desirable performance, they need to trust and depend on one another. The film production process can be viewed as a “team sport” (i.e. based on the collaboration between various departments), and even though some of the departments are often underestimated, the filmmakers claim to be aware that film’s success is based on the synergy created between all the roles. However, in practice this synergy is often missing, and the lack of care about the relationships between various members can influence the whole film production process.

Crucial to this process are the leadership roles of both directors and producers. The directors’ role is to create a film according to their artistic vision; they provide guidance and leadership to the other members of the film crew in order to achieve the highest standard. Producers, on the other hand, are the main financial investors who are responsible for employing all the other members, providing financial support (e.g. buying costumes, equipment, rights to film in a specific location), and they also may have influence on the artistic vision conveyed by a director (KIPA, 2016). Even though directors and producers are both in the positions of power, they are responsible for different aspects when managing the film crews. However, for both roles it is of fundamental importance, similarly to leaders in business and sport, to be able to manage conflicts (e.g. Zhang, Cao, & Tjosvold, 2011), promote commitment (e.g. Kent & Challadurai, 2001), and build positive relationships with all the members of their team – a film crew (e.g. Din, Paskevich, Gabriele, & Werthner, 2015).

Moreover, it is important to also understand that “success” is not always implied in terms of money, box office records and career (Galazka, 2012). In sport, success may be perceived as winning (achieving the best score), defeating an opponent, or prime performance (understood as showing excellent level of performance in the most demanding conditions; Taylor, 2001). However, as pointed out by Hamilton and Robson (2006), performing arts differ from sport in terms of the way success is perceived, as there is no “perfect score” measured; in film, achieving artistic excellence perceived subjectively by the individuals creating a film can be viewed as an indicator of success. Usually, the final outcome (i.e. film) would be assessed based on the subjective reactions and perceptions of the audience, film critics, and peers. The same film may appeal differently to various individuals, which is why the film performance forecasts are sometimes fallible (Swami, 2006). Even though the filmmakers strive for awards in film competitions (e.g. Berlin International Film Festival; Cannes Film Festival), and the number of awards correlates positively with the consequent movie guide ratings (Simonton, 2004), those awards are also subject to a number of factors (e.g. opportunities to promote a film, which is connected with film’s budget; cultural factors; how popular a specific topic is in a given year; originality). As Hamilton and Robson (2006, p. 255) suggested: “Although commercial success in the arts is often similar to playing the lottery, focusing on peak performance can help talented artists come closer to achieving this goal by mastering the aesthetic and technical requirements”. For those reasons, filmmakers could find it beneficial to learn how to embrace task orientation (Nicholls, 1984a; Nicholls, 1984b) and focus on the psychological techniques which may help them in dealing with varying amounts of success.

Even among professionals and the eminent, success is not guaranteed and may depend on a number of factors such as intrinsic motivation and strategies used to cope with performance stressors (Poczwardowski & Conroy, 2002) or resilience (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2012). Intrinsic motivation is an especially important factor and it has been found to be associated with positive performance and positive emotional outcomes in a group of performing artists (Lacaille, Koestner, & Gaudreau, 2007), and intrinsic motives (participating in theatre was exciting and stimulating and could lead to the accomplishment of personal goals) have been found to be more important than external motives to a group of theatre actors (Martin & Cutler, 2010). Intrinsic motivation has also been indicated as one of the necessary components of creativity (Amabile, 1996), which has been shown to be differently exhibited between eminent (e.g. Olympic level athletes) and less-skilled athletes (Gute, Gute, & Csikszentmihalyi, 2016). The future research should explore how the social environment (i.e. relationships between various filmmakers) affects intrinsic motivation, and by that, enables creativity and supports the development of one’s talent and eminence.

The filmmakers expressed their awareness regarding the importance of mental skills and how they affect their functioning; however, they tend to not engage in mental skills training. Similar results have been found in sport environment, where the researchers have found that even though athletes admit that the developmental of mental skills is important, they are reluctant to engage in training (e.g. Green, Morgan, & Manley, 2012). Some of the reasons put forward are: being judged by coaches and teammates (Green et al., 2012); (lack of) confidence in sport psychology consulting (Martin, Kellmann, Lavallee, & Page, 2002); and personality factors (neuroticism, conscientiousness, and openness; Ong & Harwood, 2017). In the present study, the filmmakers also stated that lack of information and understanding regarding how mental skills can be improved was a major reason preventing them from engaging in such development. Moreover, they were not convinced that psychological skills training is crucial for them; however, the more experienced and older participants disclosed that they had experience collaborating with psychotherapists when they found they were unable to deal with stress, anxieties, and substance abuse on their own, and when those disorders affected their ability to work. It is therefore important to collaborate with, for example, film schools to educate filmmakers about the benefits of mental skills development, and to provide mental skills training in the early stages of filmmakers’ development. Skills and techniques such as arousal management, goal setting, imagery, or relaxation can prove essential to sustain healthy wellbeing, optimize the experience of flow (Csikszentmihályi, 1990), effectively face the demands placed on the filmmakers by the film production process and cope with critics’ reviews (Hamilton & Robson, 2006).

Limitations & Future

research Directions

Even though the majority of the departments included in a film production were represented in the data collection process, some were more included than others. For example, 20 actors took part in the interviews, in comparison to only five sound technicians and four costume designers. In the future, the under-represented groups should be investigated further, especially taking into account their concerns about not being fully understood. Coffey (2014) in “An Open Letter from your Sound Department” pointed out a number of obstacles that the sound technicians face when recording audio in hope of educating directors and producers. His request: “We are not asking for any special powers on set, just equal respect for our craft” resonates with the generated grounded theory, as it portrays the film making process as a collaboration between all the members who should be treated with respect and appreciation.

Furthermore, in the present study the focus was on a film production crew as a group/team; however, there is still a need to explore the individual characteristics and factors which drive various members of the film production. In the literature regarding the psychology of performing artists in the film domain, the focus is predominantly on the actors (e.g. Hamilton & Robson, 2006; Wilson, 1994); however, as the presented grounded theory has shown, other filmmakers make it possible for a film to be created and to achieve success. Therefore, future studies and practice of performance psychologists should not be exclusively available to actors and actresses, but to all members of a film production.

The present study constituted only a first step in the exploration of the dynamics which affect and govern a film production process. Future research should investigate more closely the relationships between specific conditions, factors, and the indicators of the quality of collaboration. For example, it could prove useful to learn how the communication style of directors affect the sense of togetherness. In sport, the inspirational communication style used by coaches has been shown to affect feeling of pride and unity (e.g. Smith, Figgins, Jewiss, & Kearney, 2018), and the emotional messages embedded into a coach speech may affect participants’ sense of team efficacy (Vargas & Bartholomew, 2006). It could be posited that a director who conveys an exciting vision for the film in an inspirational way, could also help his fellow filmmakers achieve a sense of cohesion, as well as understand the sacrifices to be made in order to achieve that goal (e.g. severe weight loss/gain by an actor for a specific role).

Conclusions

The EFPC grounded theory does not constitute a template which would guarantee a successful film production process; it suggests that the dynamics which govern a film production process are complex, yet the included factors are malleable and can be developed through a systematic training and reflective approach. Moreover, any psychologist who wishes to begin a collaboration with filmmakers should first attempt to understand this performance environment and tailor their intervention to the individual needs of the performer (Hamilton & Robson, 2006).

References

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to “The Social Psychology of Creativity.” Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Aoyagi, M. W., & Portenga, S. T. (2010). The role of positive ethics and virtues in the context of sport and performance psychology service delivery. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41(3), 253-259. doi: 10.1037/a0019483

Aoyagi, M. W., Portenga, S. T., Poczwardowski, A., Cohen, A., & Statler, T. (2012). Reflections and directions: The profession of sport psychology past, present, and future. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(1), 32-38. doi: 10.1037/a0025676

Brass, D. J. (1995). Creativity: It’s all in your social network. C. M. Ford, D. A. Gioia, eds. Creative Action in Organizations. Sage, Thousands Oaks, CA, pp. 94–99.

Brol, M. & Skorupa, A. (2018). Znaczenie filmu w pracy psychologów i psychoterapeutów [The meaning of film in the work of the psychologists and psychotherapists]. In A. Skorupa, M. Brol & P. Paczyńska-Jasinska (Eds.) Film w terapii i rozwoju. Na tropach psychologii w filmie [Using film in a therapy and development.]. Vol. 2 (pp.183-203). Warszawa: Diffin.

Carron, A., Widmeyer, W., & Brawley, L. (1985). The Development of an Instrument to Assess Cohesion in Sport Teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7(3), 244-266.

Cattani, G., & Ferriani, S. (2008). A Core/Periphery Perspective on Individual Creative Performance: Social Networks and Cinematic Achievements in the Hollywood Film Industry. Organization Science, 19(6), 824-844.

Caves, R. E. (2000). Creative Industries: Contracts Between Art and Commerce. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Csikszentmihályi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: HarperCollins.

Csikszentmihályi, M. (1999). Implications for a systems perspective for the study of creativity. R. J. Sternberg, ed. Handbook of Creativity. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 313–335.

Clark, D. (1989). Performance-Related Medical and Psychological Disorders in Instrumental Musicians. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 11(1), 28-34. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm1101_4.

Coffey, J. (2014). An Open Letter from your Sound Department – A Production Sound Manifesto written by audio professionals. Retrieved from http://filmsound.org/production-sound/openletter.htm

Coget, J. F., Haag, C.., & Gibson, D. E. (2011). Anger and fear in decision-making: The case of film directors on set. European Management Journal. 29(6), 476-490.

Cohen, A. J. (2002). Music cognition and the cognitive psychology of film structure. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 43(4), 215-232.

Corbin, J. C., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Din, C., Paskevich, D., Gabriele, T., & Werthner, P. (2015). Olympic Medal-Winning Leadership. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 10(4), 589-604. doi: 10.1260/1747-9541.10.4.589

ECORYS Polska Sp. z o.o. (2017). Bilans kompetencji sektora filmowego – między potrzebami branzy a mozliwosciami edukacji [The balance sheet of competences in the filmmaking sector –between the requirements of the industry and educational opportunities]. Retrieved from https://www.pisf.pl/files/dokumenty/Raport_badanie_kompetencji_PISF_2017/Raport_PISF_2017_Bilans_kompetencji_sektora_filmowego__midzy_potrzebami_brany_a_moliwociami_edukacji.pdf

Elsbach, K. D., & Kramer, R. M. (2003). Assessing creativity in Hollywood pitch meetings: Evidence for a dual-process model of creativity judgments. Academy of Management Journal, 46(3), 283-301.

Ferriani, S., Corrado, R., & Boschetti, C., (2005). Organizational Learning Under Organizational Impermanence: Collaborative Ties in Film Project Firms. Journal of Management and Governance, 9, 257-285.

Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2012). A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise,13, 669-678.

Galazka, P. (2012). Psychologia osiągnięc dla aktora w okresie edukacji [Performance psychology for an actor during the time of education] (Unpublished master’s thesis). Państwowa Wyzsza Szkoła Filmowa, Telewizyjna i Teatralna im. Leona Schillera w Lodzi: Wydział aktorstwa, Lodz.

Green, M., Morgan, G., & Manley, A. (2012). Elite rugby league players’ attitudes towards sport psychology consulting. Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, 8, 32-44.

Gute, G., Gute, D., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2016). Assessing Psychological Complexity in Highly Creative Persons: The Case of Jazz Pianist and Composer Oscar Peterson. Journal of Genius and Eminence, 1(1), 16-27.

Hadida, A. L. (2009). Motion picture performance: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(3), 297-335. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00240.x

Hamilton, L., & Robson, B. (2006). Performing Arts Consultation: Developing Expertise in This Domain. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37(3), 254-259. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.37.3.254

Hays, K. F. (2002). The Enhancement of Performance Excellence Among Performing Artists. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14(4), 299-312. doi: 10.1080/10413200290103572

Hays, K. F., & Brown, C.H. (2004). You’re on! Consulting for peak performance. The Sport Psychologist, 18, 471-472.

Hays, K. F. (2006). Being fit: The ethics of practice diversification in performance psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37, 223-232. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.37.3.223

Hays, K. F. (2017). Performance Psychology with Performing Artists. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Holt, N. L., & Tamminen, K. A. (2010). Moving forward with grounded theory in sport and exercise psychology. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11, 419-422.

Kent, A., & Chelladurai, P. (2001). Perceived Transformational Leadership, Organizational Commitment, and Citizenship Behavior: A Case Study in Intercollegiate Athletics. Journal of Sport Management, 15(2), 135-159. doi: 10.1123/jsm.15.2.135

Kogan, N. (2002). Careers in the performing arts: A psychological perspective. Creativity Research Journal, 14, 1–16.

Kremer, M. (1993). The O-Ring Theory of Economic Development. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 551–575.

Lacaille, N., Koestner, R., & Gaudreau, P. (2007). On the value of intrinsic rather than traditional achievement goals for performing artists: A short-term prospective study. International Journal of Music Education, 25(3), 245–257.

Lennox, P. S. & Rodosthenous, G. (2016). The boxer–trainer, actor–director relationship: an exploration of creative freedom. Sport in Society, 19(2), 147–158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1067769.

Loska, K. (1998). Kino gatunkow: wczoraj i dzis [Cinema of the genres: yesterday and today]. Krakow: Rapid.

Lubell, A. (1987). Physicians Get in Tune with Performing Artists. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 15(6), 246-256. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1987.11709389.

Martin, J. J., & Cutler, K. (2002). An Exploratory Study of Flow and Motivation in Theater Actors, Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14(4), 344-352.

Martin, S. B., Kellmann, M., Lavallee, D., & Page, S. J. (2002). Development and psychometric evaluation of the sport psychology attitudes-Revised form: A multiple group investigation. The Sport Psychologist, 16, 272-290. doi:10.1123/tsp.16.3.272

Montuori, A., & Purser, R. (1996). Social Creativity: Prospects and Possibilities, Vol. 1. Hampton Press, Cresskill, NJ.

Mroz, B. (2008). Osobowosc wybitnych aktorow polskich. Studium roznic miedzygeneracyjnych [Personality of the leading Polish actors. The study of the cross-generational differences]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Mroz, B. (2015). 20 lat pozniej – osobowosc i hierarchia wartosci wybitnych aktorow polskich. Badania podłuzne [20 years later – personality and the hierarchy of values of the leading Polish actors. Longitudinal studies]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Mroz, B., Kociuba, J., & Osterloff, B. (2017). Sztuka aktorska w badaniach psychologicznych i refleksji estetycznej [The art of acting in psychological research and aestetic reflection]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Nicholls, J. (1984a). Conceptions of ability and achievement motivation. In R. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education: Student motivation, Vol. I (pp. 39-73). New York: Academic Press.

Nicholls, J. (1984b). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91, 328-346.

Nowak, A., & Vallacher, R. R. (1998). Dynamical social psychology. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Ong, N. C. & Harwood, C. G. (2017). Attitudes toward sport psychology consulting in athletes: Understanding the role of culture and personality. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 7(1), 46-59.

Poczwardowski A. & Conroy, D. E. (2002). Coping Responses to Failure and Success Among Elite Athletes and Performing Artists, Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14, 313-329.

Poczwardowski A., Nowak A., Parzelski D., & Klodecka-Rozalska J. (2012). Psychologia sportu pozytywnego [The Psychology of Positive Sport]. Sport Wyczynowy, 2, 68-81.

Portenga, S. T., Aoyagi, M. W., & Cohen, A. B. (2016). Helping to build a profession: A working definition of sport and performance psychology, Journal of Sport Psychology in Action.

Portenga S. T., Aoyagi M. W., Balague G., Cohen A. & Harmison B. (2011). Defining the Practice of Sport and Performance Psychology. American Psychological Association Division 47, 9.

Richard, V., Abdulla, A. M., & Runco, M. A. (2017). Infuence of Skill Level, Experience, Hours of Training, and Other Sport Participation on the Creativity of Elite Athletes. Journal of Genius and Eminence, 2(1), 65-76.

Salas E., Dickinson T. L., Converse S. A., & Tannenbaum S. I. (1992). Toward an understanding of Team Performance and Training, In R. W. Swezey & E. Salas (Eds.). Teams: their training and performance. (pp. 3-29) Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Sarkar, M. and Fletcher, D., (2014). Ordinary magic, extraordinary performance: psychological resilience and thriving in high achievers. Sport, Exercise and Performance Psychology, 3 (1), pp.46-60.

Short, S., Sullivan, P., & Feltz, D. (2005). Development and Preliminary Validation of the Collective Efficacy Questionnaire for Sports. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 9(3), 181-202. doi: 10.1207/s15327841mpee0903_3

Simonton, D. K. (1984a). Artistic creativity and interpersonal relationships across and within generations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(6), 1273–1286.

Simonton, D. K. (2004). Film Awards as Indicators of Cinematic Creativity and Achievement: A Quantitative Comparison of the Oscars and Six Alternatives. Creativity Research Journal, 16(2-3), 163-172.

Simonton, D. K. (2009). Cinematic success criteria and their predictors: The art and business of the film industry. Psychology & Marketing, 26(5), 400-420.

Smith, M., Figgins, S., Jewiss, M., & Kearney, P. (2018). Investigating inspirational leader communication in an elite team sport context. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 13(2), 213-224. doi: 10.1177/1747954117727684.

Soila-Wadman, M., & Koping, A. S. (2009). Aesthetic Relations in Place of the Lone Hero in Arts Leadership: Examples from Film Making and Orchestral Performance. International Journal of Arts Management. 12(1), 31-43.

Solomon, M. R., Pruitt, D. J., & Insko, C. A. (1984). Taste versus fashion: The inferred objectivity of aesthetic judgments. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 2, 113-125.

Strauss A., & Corbin J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sullins, E. S. (1991). Emotional Contagion Revisited: Effects of Social Comparison and Expressive Style on Mood Convergence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(2), 166-174.

Swami, S. (2006). Invited commentary: research perspectives at the interface of marketing and operations: applications to the motion picture industry. Marketing Science, 25, 670-673.

Szmagalski, J. (1998). Przewodzenie małym grupom. Działanie grupowe [Small group leadership. Group action]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Centrum Animacji Kultury.

Tesluk P., Mathieu J. E., Zaccaro S. J., & Marks M. (1997). Task and aggregation issues in the analysis and assessment of team performance. In M. T. Brannick, E. Salas & C. Prince (Eds.) Team performance assessment and measurement: theory, methods and applications. (pp. 197-224) Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Talbot-Honeck, C. & Orlick, T. (1998). The Essence of Excellence: Mental Skills of Top Classical Musicians. Journal of Excellence, 1, 61-75.

Taylor, J. (2001). Prime sport: Triumph of the athlete mind. New York: Universe.

Totterdell, P. (2001). Catching Moods and Hitting Runs: Mood Linkage and Subjective Performance in Professional Sport Teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(6), 848-59.

Vargas, T. M. & Bartholomew, J. B. (2006). An exploratory study of the effects of pregame speeches on team efficacy beliefs. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 36, 918-933.

Weed, M. E. (2009). Research quality considerations for grounded theory research in sport & exercise psychology. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10, 502-510.

Weed, M. E. (2017). Capturing the essence of grounded theory: the importance of understanding commonalities and variants, Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 9(1), 149-156.

Wilson, G. D. (1994). Psychology for performing artists: Butterflies and bouquets. London and Bristol, PA: Jessica Kingsley.

Wojnicka J., & Katafiasz, O. (2005). Slownik wiedzy o filmie [Film knowledge dictionary]. Bielsko-Biala: Wydawnictwo Park.

Young, S.D. (2012). Psychology at the Movies. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Zablocki, M. (2013). Organizacja produkcji filmu fabularnego [The organization of the feature film production]. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Wojciech Marzec.

Zarzad Krajowej Izby Producentow Audiowizualnych – KIPA (n.d.). Rezyser [Film director]. Retrieved from: http://kipa.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/rezyseria_05_rezyser.pdf.

Zhang, X., Cao, Q., & Tjosvold, D. (2010). Linking Transformational Leadership and Team Performance: A Conflict Management Approach. Journal of Management Studies, 48(7), 1586-1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00974.x

Zickar, M., & Slaughter, J. (1999). Examining creative performance over time using hierarchical linear modeling: An illustration using film directors. Human Performance, 12(3-4), 211-230. doi: 10.1080/08959289909539870

Zienowicz A., & Serwotka E. (2017). Psychologia osiagniec dla tworcow filmowych [Performance psychology for the filmmakers]. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Wojciech Marzec.

1 Depending on whether the project is a director’s cinema project or a producer’s cinema project, the director’s and the producer’s impact on the personal composition of the crew will vary.

2 The schedule of film production works, broken down into all days of the shooting period (production stage).

Figure 1.

Grounded theory of effective film production collaboration in Poland.